Reducing court administration burdens through automation

This piece was originally written for the Thomson Reuters Institute. You can read the original here.

Courts process thousands of routine filings each day, and many courts continue to rely on highly manual processes; yet emerging automation and AI tools present an opportunity to increase efficiency, improve service delivery, and strengthen access to justice

Bringing automation and AI-powered tools to data entry, case-filing processing, and updating court management systems over the next few years could help court professionals use their time more efficiently, according to the Staffing, Operations and Technology: A 2025 survey of State Courts from the Thomson Reuters Institute and the National Center for State Courts (NCSC).

Indeed, the report found that alleviating this invisible administrative burden could help professionals reclaim as much as nine hours per week over the next five years. As private sector law firms embrace automated technology, public sector legal departments and courts risk falling further behind.

The time for innovation is now, as caseloads mount, case complexity increases, and retirements and staffing shortages continue to plague courts. Fortunately, administrative professionals are beginning to warm up to targeted automation efforts and AI-powered tools to expand their efficiency.

The cost of administrative burdens

A Georgetown University study produced for the Administrative Conference of the United States defines administrative burdens as “onerous experiences people encounter when interacting with public services.” And unfortunately, many people do not access the rights or benefits to which they are entitled because of these onerous administrative processes within stressful, frustrating, and overwhelming government systems. In a legal context, administrative burdens hinder access to justice. In fact, low-income Americans did not receive any legal help or enough legal help for 92% of the problems that impacted their lives, according to the Georgetown study.

Recent years have seen a dramatic rise in self-represented (pro se) litigants in civil cases. Given this, the processes that were designed for navigation by attorneys and legal and court professionals need to be simplified to reflect the needs of non-professional court users. A Pew Research study on experiences with state courts in particular notes that court users strongly desire courts to be easier to navigate. Even among those who had previous court experience, 50% indicated that it was a little hard or very hard to navigate court paperwork and steps in a case.

A modernizing court workforce

Millennial-aged workers constitute approximately 75% of the workforce and are the most prevalent court users today and in the foreseeable future. As digital natives, this generation expects modern tools when navigating the legal system.

A State of the State Courts poll commissioned by the NCSC last year found that large percentages of registered voters surveyed support increased use of AI chatbots to answer court FAQs (with 63% saying this), using AI to translate court documents into other languages (64%), and using AI to break down complex legal jargon and make information more accessible (71%).

Further, this lack of modernization in courts has consequences for judges and court professionals as well. Court staff are feeling strained by their workload, and many report simply not having enough time to catch up. More than half (57%) of court professionals and administrative staff reported not having enough time, according to according to the Staffing, Operations and Technology report.

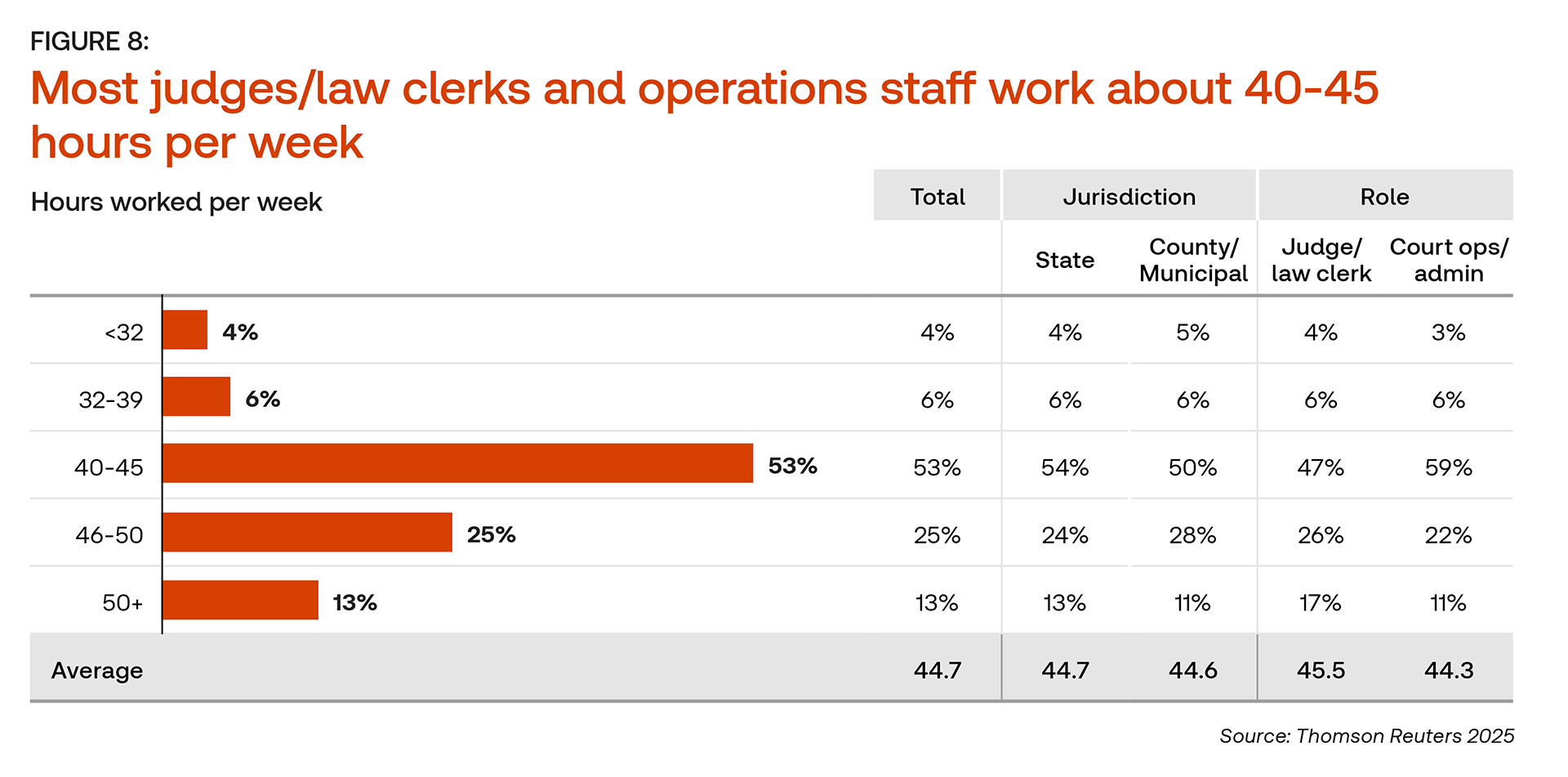

The report also found that 91% of court staff report working more than 40 hours each week, with about one-third of them working more than 46 hours per week.

Given all this, the pressure courts are under to modernize is understandable; however, it should be looked at as an impetus for improvement: Courts face a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reimagine their workflows.

Resources available to fund statewide technology improvements

Several states leveraged one-time resources available through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) to fund major investments in court technology. The Kentucky courts’ Administrative Offices of the Courts (AOC), for example, used $38 million to update a two-decade-old in-house case management system. (The AOC is the operations arm of the state court system, which supports 3,000 employees and more than 400 elected justices, judges, and circuit court clerks.) Kentucky courts’ AOC selected a third-party technology provider that offers online tools for judges, circuit court clerks, attorneys, as well as a tool for pro-se litigants.

On the other hand, Arkansas courts’ AOC opted to build its own in-house court management system, as the cost was significantly less than vendor rates. Initial estimates to upgrade a legacy system were $70 million, and Arkansas was able to build its own for $20 million, funded through ARPA appropriations that came from the state legislature. Indeed, Arkansas has been a leader in court technology for more than 20 years and signed contracts for automated document redaction more than a decade earlier.

The state courts new customized cloud-based solution incorporates multiple vendors, and the development process (now two years underway) has launched Contexte Case Management, an internal facing tool, and Search ARCourts, a public-facing case information tool. All AR appellate and circuit courts are using Contexte and nearly half of district and juvenile courts already have implemented the system.

Moving forward, slowly and thoughtfully

While private sector legal technology has advanced quickly, courts face unique challenges that often make off-the-shelf solutions an inadequate fit. Investment in court modernization must balance the efficiency gained with fiscal responsibility around such investment.

Successful implementation in courts will take cultural, procedural, and budgetary shifts. Internally, collaboration between judges, administrators, and IT staff is essential; and externally, any public-facing tools should center around user experience and ease-of-use, perhaps offering a dedicated customer service team to guide users so that technology reduces complexity rather than adding to it.

The real return on investment in court systems will be realized when all users can access justice more easily, equitably, and reliably.